This Too Shall Pass: Understanding Passing a Kidney Stone

Passing a kidney stone can be miserable. Some female patients tell us stone passage is worse than childbirth. So, what does it mean for a kidney stone to pass, and why don’t we have a better solution?

What is a Kidney Stone?

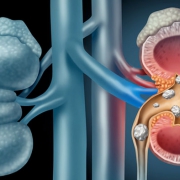

Kidney stones, as the name implies, form in the kidney. They can stay in the kidney, but sometimes will drop out of the kidney and into the tube that connects the kidney to the bladder, called the ureter. The ureter is narrow, and as such, can unfortunately be easily blocked by a stone. A blockage in the ureter can lead to a backup of urine in the kidney (the medical term is “hydronephrosis”). This leads to dilation of the kidney and can cause severe pain and nausea.

Small kidney stones have a high likelihood of passing out of the ureter and into the bladder with a little time. Once stones make their way into the bladder, they are usually urinated out without much issue (the urethra—the tube you urinate out of—is much larger than the ureter).

If a stone can make this journey, you can avoid a trip to the operating room for a procedure to remove it. Drinking a lot of fluid, and in some cases taking a prescription medication that dilates the ureter, can help the stone pass. If your other kidney is healthy, the obstructed kidney can withstand a few weeks of blockage without long-term damage.

What Can We Do About Them?

So, what happens if a stone is too big, the pain or nausea too severe, or if you don’t want to wait for a stone to pass? Fortunately, we have a minimally invasive option to remove obstructing stones. This procedure, called ureteroscopy with laser lithotripsy, allows urologists to remove stones in the operating room with a small flexible camera and thin laser inserted through your urinary tract. No cuts, no incisions. Often, a stent must be left behind temporarily in the ureter after these procedures to decrease risk of swelling, blockage, and infection. These stents, which extend from the kidney to the bladder, are temporary and usually removed within a week or two in the office. Stents can cause some discomfort, blood in the urine, and urinary frequency, which is part of the rationale for letting a small stone try to pass. Depending on the size and position of the stone, along with the severity of symptoms, you and your urologist can help determine whether stone passage may be right for you.

Kidney stones can be miserable, but you don’t need to face them alone. If you think you may be passing a kidney stone, call Georgia Urology’s Kidney Stone Hotline—a 24/7 appointment scheduling line— at 1-855-STONE11 (1-855-786-6311).